Many mysteries still surround the history of the firm, as its archives have disappeared. A document of the Petrograd Commune dated March 1919 states that “the owners of the firm ran away after hiding their documents and instruments.” The documents of the firm's head office might indeed have been hidden somewhere in Saint Petersburg or its environs — for instance at Agathon Carlovich Fabergé’s house at Levashovo — however no trace of the Faberge archives has yet been found in the west.

After publication of the works of H.C Bainbridge (1949) and A.K. Snowman (1953), it was generally considered that the history of the firm had been elucidated as far as possible, and that no further information could be expected to emerge from any source.

Then, a miracle happened. In February 1990, Valentin V. Skurlov found in the archives of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR (now the Russian Academy of Sciences), in the section of the “Fond” of Academician A.E. Fersman, an unknown manuscript, written not by a mere employee of the Fabergé firm, but by its chief workmaster. It was entitled Gemstone carving, jewelry and gold and silverwork of the House of Fabergé.

After analysing the text of Academician A.E. Fersman’s book Outlines of a History of Stone (Moscow, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1954, Vol. I), V.V. Skurlov smelled a rat: the chapter dealing with the work of the Faberge gemstone carvers had not been written by the Academician, but by somebody else. The difference between the literary style and language of this chapter and the rest of A.E. Fersman's writings was striking. This gave Skurlov the idea of looking through the material used to prepare the book in the Academician's archives, and he had the good fortune to discover Franz P. Birbaum's manuscript, written at the request (or perhaps the command?) of Academician Fersman in 1919 for a projected four-volume monograph, Russian Gemstones.

It would appear that after A.E. Fersman's death in 1943, his literary executors included some material from F.P. Birbaum's manuscript in Outline of a History of Stone, without acknowledging it’s author. Fersman's book contains 25-30% of Franz Birbaum's text, mainly related to the firm's gemstone carving activities. The manuscript also quoted unique information that answered questions that have mystified Faberge students throughout the world for over half a century.

The mystery started with H.C. Bainbridge's earliest publication, entitled Twice Seven in the 1930s.

The new information relates primarily to Birbaum's details about the designers, workmasters and workshop owners. His manuscript mentions 84 people, 33 of whom were previously unknown to researchers.

We can only bitterly regret that the manuscript was not brought to light earlier, as at least some of the Faberge collaborators on F.P. Birbaum's list were still alive in the 1970s. Those unequalled specialists and witnesses of Faberge history could have answered many questions, because they had worked in person with the great jeweller.

Чтобы прочитать эту статью на русском языке, нажмите здесь.

* * *

Franz Birbaum’s memoirs, 1919

Translation by H.S.H. Princess N. Galitzine, Mrs. Nigel Heseltine

(Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book, pp. 297-311)

Used with kind permission of the authors.

The Fabergé jewelry firm was founded in Saint Petersburg in 1848 by Gustav Fabergé. It started as a modest workshop and its production was on a par with its size — fashionable but crude — gold bracelets, brooches and pendants in the shape of belts with buckles, quite skillfully combined and set with gems or enameled; such examples of jewellery are to be found among old designs of the firm.

It was an enterprise similar to many others, but when Gustav Faberge’s sons Carl and Agathon joined the business, the workshop was extended and special care was devoted to the artistic aspect of manufacturing. Both the brothers, who had received higher artistic education abroad, were eager to put their knowledge into practice.

Carl Gustavovich, a convinced admirer of classical styles (which he has remained up to the present day), devoted all his attention to them, while Agathon Gustavovich, being of a more lively and impressionable nature, sought inspiration everywhere — in ancient works of art, in oriental styles which were then less well known, and in Nature.

His surviving designs bear witness to his unremitting application and never-ending search: ten and even more variations of the same motif can often be found; however simple an object might be, he would consider it in all its aspects and would not proceed to its manufacture until he had exhausted all its possibilities and had calculated all its effects. Suffice it to say that in jewellery design he seldom limited himself to a drawing, but preferred molding a wax model and applying the appropriate gems to it in order to bring out the beauty of each stone: large stones might lie about for weeks awaiting drawings of their settings. Every gem had to be set In the specific article, be it a brooch, ring, necklace or tiara which would show off its best qualities, since in one article the gem might remain unnoticed, while in another all its natural beauty would be seen at its best. Then the problem of the «entourage»had to be solved — the problem of surrounding gems, which were intended not to eclipse the main gem, but to enhance it and also to conceal its possible defects; eventually the gem had to be put into the position which would provide the maximum reflection.

Such were the methods used by Agathon Gustavovich, with whom I am happy to have worked for some years. Equal attention was naturally paid to execution, and not infrequently an article was rejected because of a minute fault and was thrown back into the crucible. Among the first works that brought fame to the Faberge brothers were the replicas of the Kerch jewelry commissioned by the German Emperor Wilhelm II. The reproduction of the famous necklace with pendants in the shape of amphorae attracted the particular attention of connoisseurs and courtiers, since its execution required great precision and the use of long-forgotten ancient methods. The Fabergé brothers brilliantly overcame all the difficulties and soon received commissions to reproduce sets of Kerch jewelry.

The Hermitage Museum with its “Golden Treasury” served as an excellent school for the Fabergé jewelers: after the Kerch collection they began studying jewelry of all the epochs represented, especially those of Empresses Elizabeth and Catherine II. Many of those articles were copied with great precision and were later used as models for the creation of new compositions. Some of the best proofs of the artistic excellence of these objects are the many commissions from foreign antiquarians who laid down conditions that the objects should be neither hallmarked nor stamped with the name of the firm: such orders were naturally turned down.

The compositions retained ancient styles but were applied to modern articles. Cigarette-cases and toilet-cases took the place of snuff-boxes; instead of knick-knacks the firm produced clocks, ink-wells, ashtrays, buttons for electric bell-pushes and so forth. The firm’s output increased rapidly, and the manufacture of gold articles was soon concentrated in a workshop separate of that of silver items. Overloaded with work, the Faberge brothers of course could not manage all the shops themselves, so they decided to establish independent workshops.

Their owners were committed to work only for their firm, making use of its sketches and models. Thus the jewelry workshops of Holströmand Thielemann, the goldsmiths’ workshops of Reimer, Kollin and Perkhin, and the silversmiths’ workshops of Rappoport, Aarne, Wakewä et al. were founded.

Each workshop was assigned a specific type of production and their apprentices specialized in different kinds of work. The output of all the workshops bore the mark of the workmaster, and the trademark of the firm, if there was room enough. The workshops of Reimer, Kollin and Holström were the first to be established. Refiner's workshop began its activity when the firm was headed by Gustav Fabergé (I have already mentioned its specialization). Kollin's workshop made replicas of the Kerch antiquities and similar items; at that time gold settings for large carved carnelians and other kinds of agates were used in brooches, necklaces and other items and were made of high-quality matte gold in the shape of beaded or roped hoops with pierced or filigree motifs.

The third workshop, making jewellery only, was run by Holmström the Elder and by his son after his death.

The workshop was famous for its great precision and exquisite technique: such faultless gem-setting is not to be found even in works by the best Paris jewellers. It should be noted that even if some of Holmström's works are artistically somewhat inferior to those of Parisian masters, they always surpass them in technique, durability and finish.

During more than half a century the manner of manufacturing jewellery had been changing radically: at first, in the 1860s, brilliants and coloured stones were only a supplement to gold, but then the traditions of the 18th and early 19th centuries were revived and the workshop began producing items composed exclusively of brilliants set in silver: these settings were first of all designed to create an illusion, bezels being mirror-finished and gently sloped to produce the impression of a large stone, but this deception soon palled, particularly since the illusion of the size of the stone vanished as the silver tarnished.

The methods were then changed, and the setting became almost invisible, with a minimal thickness of metal. The favourite motifs were sprays of flowers, ears of wheat, skilfully tied bows; petals and leaves were shaped by forging and setting brilliants, carefully chosen so that their relief contributed to the final shape. This was the best time for diamond jewellery, all the objects of the period being noted for their vivid outlines which could be clearly seen even at a distance. Among the fashionable ornaments were tiaras, aigrettes, collarshaped necklaces, breast-plates, corsage ornaments, clasps and large bows.

The next influence was that of the Empire style characterized by dryness, the strict meandering and convoluted lines not allowing for the use of reliefs, with the result that brilliants placed on the same level lost part of their fire, neutralizing each other’s interplay. The “ Stil’ Moderne” that emerged at the end of the 19th century found no broad application in the firm’s production; dissoluteness of shapes and unrestrained fantasy bordering on the absurd could not attract designers who had become accustomed to a certain artistic discipline. We naturally acknowledge the artistic value of objects created by certain individuals such as Lalique, but we never tried to imitate him: we thought it useless and we were right, for his imitators, while unable to produce anything comparable to his masterpieces, lost their own originality. With the exception of some pieces made for special commissions, the firm produced no important articles of that kind. Enthusiasm for the “Modern style” began subsiding, banalities of endless copies and lack of content (...) (the sentence is incomplete),and was followed by a passion for ornamentation with tiny brilliants and diamonds, the motifs thus studied producing an impression of a grey compact mass, even at a short distance.

This kind of work can be done only on small pieces, such as rings, bracelets and brooches, where the richness of design and perfection of separate parts can be discerned. Most of the pieces were made of fine platinum or with a platinum and silver alloy: the use of platinum was an advance, as it does not tarnish, and its beautiful grey colour enhances the whiteness of diamonds, but the abundance of straight parallel lines and concentric circles make the pieces somewhat dry and difficult to offset by a profusion of details.

A successful innovation was the use of single-faceted rectangular coloured stones, arranged in a ribbon-like narrow row, so that the metal setting remained invisible. If properly calibrated stones are used in these coloured strips, they produce a remarkable effect between diamond-pavé surfaces.

Excessive use of small brilliants is a blunder in all respects: there is none of the fire which is the main merit of diamonds, and an abundance of small stones reduces the material value of a piece, while at the same time considerably increasing the cost of the work. We can be sure that this vogue will not last and that the art of jewellery will return to sounder traditions.

GOLD ORNAMENTS

There is no sharp line between pure jewellery (i.e., pieces in which the chief part is played exclusively by gems) and gold ornaments. Of course, diamonds do not look well in gold items because of the sharp colour contrast, but coloured stones do add much to the beauty of gold. Yet gold was seldom used in ladies' jewellery, except in plain brooches, rings, chains and bracelets, and its chief application was in small household articles, such as pocket toilet-cases, scent and smelling-salt bottles, table ornaments of different kinds and in gentlemen's objects, such as cigarette-cases, cigarette-holders, walking-stick handles and seals. The treatment of gold surfaces is manifold: it can be pierced, chiselled, embossed (repousse),engraved or polished, enamelled or gem- set. As jewellery fashions changed, different styles of repoussé were applied — Louis XIV, XV, and XVI, and then the “Empire style” which because of its dryness did not lend itself to repoussé and was replaced by chiseling and engraving.

The most recent period is characterized by the wide use of enamel, which has been used together with gold from the earliest days in the cloisonné and champlevé modes. 18th century works from the Hermitage collections served as models for the application of translucent enamels over engraved and guilloché surfaces, covering large areas and sometimes even the entire surface. Such objects were unsurpassed even by those produced abroad.

At the World Exhibition («Exposition Internationale Universelle»,Paris, 1900) they had a tremendous success because of their intense tones and exquisite execution. All the exhibits were sold and the firm gained a lot of orders and clients. Manufacture of gold articles was distributed among several workshops.

KoIIin’s workshop produced replicas of Kerch antiquities and similar reproduction works. Perkhin's workshop produced chiselled and engraved works as well as settings for nephrite and other Siberian gemstone articles; it was a large- scale enterprise, and the best gold articles were produced there. Perkhin, the shop-owner, deserves special mention. He was born in the Olonets Province and came to Saint Petersburg when he was a young boy, without any education and possibly illiterate. Thanks to his hard work and natural intelligence, he made his way in the world, and from an ordinary apprentice rose to the rank of workmaster, established a workshop of his own and attracted capable assistants of various specialities. His personality combined a tremendous capacity for work, profound knowledge of his craft and persistence in solving certain technical problems. He was highly esteemed by the House and enjoyed rare authority over his apprentices.

Over a relatively short period of time he made a considerable fortune, but had no opportunity to enjoy it, because he died in a lunatic asylum in 1903.

After Perkhin's death, his workshop passed to his senior assistant and friend, H. Wigstrom. Enamelling was assigned to a special workshop run by N. A. Petrov, to whom the firm is greatly obliged for his fine work. He was the son of the enameller A.F. Petrov; from his early childhood he became acquainted with this complicated craft which is so subject to sudden failures, due to the metal, the baking process or the enamel itself. With his knowledge of all the technical details, he was able to overcome difficulties which were obstacles even to foreign enamellers, many of whom he could certainly have surpassed, had he received a proper artistic education. Work was his natural element, and unlike other masters he made ail his works himself, frequently spending nights on a task in which he was interested.

When the firm received very important commissions, the authorities sometimes sent the order abroad in order to prevent possible failures, but it was very seldom that the foreign-made article was preferable.

After the workshop was closed, Petrov was invited to the Mint to enamel badges for the Red Army. He carried out this totally uninteresting work just to earn a living, but scanty nutrition and overstrain killed him: Petrograd lost its best enameller — most probably the best enameller in Russia — and we lost a good, honest man and a toiler. The third workshop, owned by Thielemann, specialized in Jubilee and other badges, medals and orders, a specialization which was largely prompted by necessity: many of the firm's clients were dissatisfied with the extremely poor execution of mass-produced orders and badges, and applied to Fabergé’s for more artistic works. These private orders and occasional mass production of badges were the main occupation of the Thielemann workshop; when its owner died, it was taken over by the firm itself and was run by the workmaster V. G. Nikolaev.

SILVERWARE

The manufacture of silverware began with small articles, similar to gold ones, and therefore executed at goldsmiths' workshops, but special shops soon had to be opened to satisfy the growing demand. The first of these, run by the workmaster Rappoport, produced a wide variety of articles, ranging from small objects for writing tables to vases, candelabras and surtouts de table - large festive ornamentations for dinner tables.

The largest article made by the workshop was the surtout de table commissioned by Alexander III for the dowry of his daughter, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna. Sketches were made by the architect but were so unsuccessful that, in spite of all the improvements made in the working drawings, the style and proportions of those bulky expensive objects still left much to be desired.

Since the sketches had been approved by the Emperor, no radical changes could be made, and the workshop could only improve some details — thus showing yet again that artists designing such projects must have a good knowledge of manufacturing processes.

In the end Rappoport’s workshop served as the site of an interesting experiment: in 1908 its owner decided to retire, and wishing to reward his workmen for their long and faithful service, he left them the workshop and all its equipment.

The First Silversmiths' Artel was thus formed, and the firm decided to promote the experiment by granting the necessary credits and passing on commissions.

That small enterprise with only about 20 participants reflected all the drawbacks of public organizations of the time: lack of solidarity and discipline, misunderstanding of mutual interests.

After two or three years of internal discord, increases in the cost of production and a decline in its quality, the Artel ceased to exist, and its place in the firm was taken by the Armfelt workshop.

Table silver - samovars, tea sets and so forth - were produced in Wakewä’s workshop. Since the large-scale production of table silver was concentrated in the firm's Moscow factory, this workshop played only an auxiliary part.

Before 1914, 200 to 300 workmen were employed in the Saint Petersburg workshops that were scattered all over the city before the house in Morskaya was built; then the most important workshops were housed on the premises, but some of them still remained outside because of the shortage of work-space.

THE MOSCOW FACTORY

The Moscow factory, which was founded in 1887, worked in parallel with the Saint Petersburg workshops. The factory combined all the specialties which were distributed between different workshops in Saint Petersburg. Some branches, such as jewelry manufacture and gold and enamel work, were inferior in quantity and quality to those of Saint Petersburg, but silverware production was much more versatile and better organized. From 1900 on, all large-scale silverware was manufactured at the Moscow factory. Jewelry and gold articles were nothing to speak of, as they were mainly inferior versions of those made in Saint Petersburg, but silverware deserves particular attention, both because of its high artistic value and because of the model organization of production.

Moscow has always been the center of Russian silver-work and the largest enterprises of this kind are concentrated in the city. I think that this phenomenon can be explained, first by the fact that enterprises, like flowers and trees, scatter their seeds in the form of masters who organize new workshops, and secondly that wages in Moscow have always been lower than in Saint Petersburg, so that the use of hired labour was more profitable.

The main feature that distinguishes the Moscow factory from the Saint Petersburg workshops is the prevalence of the Russian folk style. One can disagree with many of its peculiarities — the absence of structured elegance and the archaic and deliberately crude execution — but all these temporary shortcomings are offset by the originality of conception and the absence of clichés in the composition.

I shall append a separate list of the most important works of this kind, which were mostly bratiny (loving cups), zhbany (jugs), kovshy (dippers), caskets, decorative vases and so forth. The subjects were figures of legendary heroes, scenes from folktales and byliny (epics), historical events and personalities — either in the form of separate figures and groups or as bas-reliefs on the objects themselves.

The works were generally cast from wax models, in one copy only. In addition, the Moscow factory produced large quantities of table silver, comparable in quality to the best foreign ware. Thanks to a wide range of punches and specially constructed powerful presses, a high degree of excellence could be achieved at a relatively low cost. The factory stored several thousand moulds of whole articles and of their separate parts.

Church silver — plate and icons also played an important part. Because of their artistic value, many of those objects were in demand even abroad, and the factory received many foreign commissions.

MANAGEMENT

The factory was situated in Kiselny Lane in the building formerly occupied by the San-Galli plant. It was divided into two departments, one for jewellery and the other for gold and silverware. Each department was headed by a workmaster, a manager and his assistant. A general office was responsible for accounting for the whole factory. The number of workers fluctuated between 200 and 300.

SOME CONCLUSIONS

Every manufacturing enterprise depends directly on the materials it uses and consequently on the industry that produces them. Thus jewelry manufacture depends on gem mining and working, and production of gold and silver ware on the quantity and quality of noble metals on the market. In this respect the enterprises in question operated under extraordinarily unfavourable conditions: mining of precious and semi-precious stones in the Ural and Eastern Siberia was in a chaotic state; deposits were not exploited but plundered; mining methods were so primitive and poorly organized that only gems found by chance and without much difficulty were mined; there were no progressive methods of mining, and gem faceting was performed by such primitive methods and was so imperfect that it could not be applied to high-quality stones, which were sent abroad for faceting and were often sold on foreign markets; thus nearly all the most important stones came to Russian jewelers from Europe, even though some of the stones were of Siberian origin, and foreign suppliers and gem-cutters were considerably overpaid.

Large amounts of semi-precious stones, such as lazurites from Bukhara and Siberia, nephrites and others, are exported to Germany and returned to our country in a polished state—a repetition of the situation of furs and leather goods, the processing of which has been transferred almost entirely to Germany.

The treatment of noble metals is almost as bad. Refining, smelting and rolling into sheets are extremely imperfect, and we have to order English silver sheets for fine work. Purchase of gold is complicated by legal prohibitions and formalities; that is why small manufacturers find it profitable to melt down gold coins in spite of the legal prohibition to do so. Although many defects of our processing may be ascribed to our imperfect equipment, a great deal of them are also due to negligence in the working process itself.

I have had the opportunity to compare the process of rolling (turning silver ingots into sheets) abroad and at home: whereas abroad this work is carried out with special care and under conditions of perfect cleanliness, our ingots and sheets lie about on dirty and even earthen floors, so that foreign matter sticks to the metal; later when it passes between the rollers, particles are impressed into the sheet. The difficulty of working with such metal can be imagined easily: in the process of polishing, encrusted foreign particles will suddenly come to the surface or fall out, leaving all kinds of marks and pits.

Even at larger enterprises, general production is organised irrationally, which leads to great losses of materials and time. In foreign enterprises, waste water is passed through six or seven filters, leaving a certain deposit of precious metal on each one, but we are satisfied with one or two filterings, so that the percentage of gold and silver losses Is much higher and represents considerable sums of money at large enterprises. Scrap and sweepings are not processed in Russia, the waste material containing precious metals being packed in barrels and sent to Hamburg where it is burnt; the sender is then paid a certain amount for the gold or silver obtained. Attempts have been made to carry out the processing in this country, but the amounts obtained were always lower than those received from abroad, probably because of the imperfection of our methods of waste treatment and refinement of precious metals.

Where the craft itself is concerned, the main obstacle to its development is the lack of artistic and technical knowledge among the masters and the absence of special schools and literature on the subject.

The existing art and technical schools do not fulfil their direct task of providing artistic and technical training to craftsmen, but produce artists or drawing masters, whereas what the industry needs above all is a body of educated masters and craftsmen.

In Western Europe, apart from the many special schools and courses for craftsmen, there is also a vast choice of literature on art and technology, as well as many periodicals on every branch of the profession. In Russia we have neither any original books on these subjects nor even translations of foreign publications. In these circumstances, what is surprising is not that our enterprises lag behind, but that they can still compete with foreign industries. Any occasional successes in this struggle are due exclusively to the individual works of certain master craftsmen.

SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT

Workmasters, workshop owners and apprentices

Although there are some individual talented workmasters, there is no corps of skilled craftsmen on which an enterprise depends. The creation of such a body, this class of educated craftsmen, is the first and most important condition of the further development of manufacture and successful competition with foreign jewellers.

I shall now take the liberty of outlining the characteristics of the Russian craftsman, with whom I have worked for more than 25 years. There can be no doubt that he surpasses his European colleagues in natural ability, but what he lacks is the conscientiousness engendered by education and general cultural development.

A craftsman who loves his craft and who is proud of it is a rarity in our country, and the result is negligence and lack of conscientiousness, self-control and diligence.

I have seen workmasters who were capable of working for 60 hours during a three-day period of emergency, but who seldom worked as smuch as eight hours a day without such stimuli as urgency or higher wages. The lack of system in the working process also reduces the productivity of our craftsmen, for whereas a Western master avoids many risks and defects by being orderly in all his procedures, the Russian craftsman is untidy and inconsistent in his methods, and he wastes a great deal of time.

Hereditary craftsmen are extremely rare in Russia: most of them came into the profession by chance. They are of rural extraction, with a primary education or are illiterate. Their children, who have managed to get some education, never follow their fathers' profession, but try to find something more profitable or respectable. This state of affairs has barred from forming a class of traditional craftsmen, and since tradition plays an important cultural role in the development of artistic crafts, the absence of such a class can only lower the general artistic level of production.

The experience of the revolutionary period should have radically changed this situation: our intelligentsia and semi-intelligentsia might have understood that the knowledge of some craft is the best security and is more reliable than a bureaucratic or other similar career, since it constitutes a capital which cannot be confiscated or nullified. The products of handicrafts will always be in demand, and this is also true of the luxury trades, such as jewellery: even nowadays, given the necessary production conditions and materials, jewellery and gold articles would enjoy unprecedented sales. Watching two craftsmen, one Russian and one Austrian, operating at identical workbenches, I observed that the Austrian, with his methodical approach and his diligence, produced three times as many articles as the Russian over the same period. If this is turned into working hours, it would seem that Austrian craftsmen could establish a three-hour working day without any fear of competition on our part. I have always asserted that not only an eight-hour, but a six- hour working day could be instituted, provided the work done during those six hours was really intensive; to confirm this, I can cite cases where the productivity for a ten- hour day of piece-work was equal to that of three working days at a lazy pace; admitting that such intensity of work is harmful and cannot be maintained daily, if it were reduced even by half, the end result would be a six-hour working day.

Our craftsmen clearly lack the knowledge and enlightenment which serve as a basis for conscientiousness and moral discipline.

Two distinct trends may be observed in the jewellery and gold and silver trades - one towards mass production and the other towards an individual artistic output. It would be mistaken, however, to conclude that the first trend excludes the possibility of producing artistic objects: on the contrary, mass production should be regarded as a means of disseminating works of art in order to make them accessible to a large number of people. For example, a plaque or medal by Rotie [Note by Birbaum: A famous French medallist of the late 19th and early 20th century] is undoubtedly a work of art, even though it is executed by stamping or by mass production. Everything depends on the quality of the original model reproduced.

The firm combined both trends in its production. Side by side with individual, manual work, methods of mechanical reproduction were also used, mainly for mass products such as table silver and for repetitive ornamentation in friezes, garlands and so forth.

I have recently experimented in combining the two working methods in the same article and obtained excellent results. The original was made by the best masters and was then reproduced in large quantities by mechanical methods; the duplicates looked very much like the original but cost half as much. The frequently expressed fear that mass production will be the end of craftsmanship is exaggerated: if articles are manufactured in the above-mentioned order (and this is the only correct way), the personal work of the master will always be necessary for the original; it must be paid at an incomparably higher rate, because the cost of the article, being subsequently divided among many hundreds of reproduced articles, will not greatly affect the final price of a single piece. In addition, however extensively mass production may develop, there will always be artistic tasks which cannot be performed by mechanical methods and will require manual work. It is true that the number of craftsmen employed will decline, but the artistic level of the remaining masters will be higher, since only the most talented ones will be able to create artistic originals.

As I have already written, the workshop owners were independent in their management, and the firm seldom interfered in the relations between the masters and their apprentices.

The common type of master was the owner-manager, but there were some exceptions, such as ...It was characteristic that all three workmasters were the best craftsmen in their workshops: they worked personally at their benches and loved their craft, being artistic by nature. Yet as we have seen, one of them was obliged to retire from his work because of nervous overstrain, another died for the same reason and none of the three succeeded in becoming rich, while workmasters of the other type amassed tidy fortunes in a short time.

The attitudes of the workmasters towards their subordinates and towards the firm was clearly revealed when the workshops had to be closed down because of the revolution and the decree on the 36 gold standard: the masters loaded on to the firm all the expenses of meeting the workers’ claims, such as three months’ wages, completely ignoring the fact that they had derived a very large income from the work of their employees.

Since most of those employees had worked for it, however indirectly, the firm met all the claims for a long time, and the workshops were closed with the employees' consent without any incidents. The master-owners adopted a passive attitude to anything that was notrelated to their profit; there was no organization among them, and no solidarity even in defending their own interests.

The existing jewelers’ association did not contribute to their unity: when apprentices at a workshop submitted their claims to their workmaster, he did not abide by any resolutions of the association, but rejected or met the workers’ claims taking only his profit into account; social and educational problems met with no support or understanding among the majority. The journal «Yuvelir» («The Jeweller»), founded by a small group of jewellers, mostly retailers, had to cease to exist, as did the Society for the Promotion of Artistic and Industrial Education. Such was the condition of the trade before 1914, but the war raised a panic. Even large workshops and firms reduced their production, supposing not without reason that there would be no demand for such luxuries as jewellery and gold ornaments. Yet even then, old experienced traders who had survived earlier wars pointed out that on the contrary in wartime, when State orders produce an abundance of bank notes which are readily used to purchase gold and diamonds, speculation and stock-exchange operations lead to the emergence of nouveaux richeswho hasten to acquire all kinds of luxury goods. These people were right and the phenomenon continues to thisday. Jewelry sales stagnated only in the first year of the war, during which the House of Fabergé decided to convert its production to war-time needs and submitted certain proposals to the War Department. The firm had to wait a year for a reply; meanwhile it had to find some occupation for its employees; among the palliatives found was the manufacture of copper articles, such as cruets, plates, mugs and snuffboxes.

The sole aim of this production was to provide work to several hundreds of apprentices. Any idea of profit was naturally out of the question, but the loss was not significant. If the authorities of the firm had been less patriotic and had taken account of all the confusion surrounding the Commissariat and military orders, they could have used the year of trade stagnation to produce large stocks of precious objects to be sold at great profit during the following years.

It was only during the second year of the war that the firm obtained military orders. The Moscow silverware factory was re-equipped and an additional workshop was opened in Saint Petersburg. At the same time, one of the work- masters, the jeweler Holmström, opened a workshop which produced “Pravatz” syringes.

Military orders were carried out by the remaining master jewelers and silversmiths and by newly employed workers; the activities of the factory and workshops continued until the beginning of the Revolution. They produced shock- tubes, time-tubes, grenades and parts of various devices. The business was difficult to start, but very soon our manufacture was quoted as an example of precision and accuracy.

I have just mentioned this episode as an example and will now return to the firm's basic manufacture, in order to give some idea of the organization of the workshops.

Every workshop employed an average of 40 to 60 apprentices, and specialists were distributed as follows:

20 to 30 mounters,

3 engravers,

3 embossers,

5 gem-setters,

5 polishers,

1 or 2 guillocheurs,

1 turner.

The specialists were also subdivided. Thus, some mounters were cigar-case makers, specializing in the manufacture of boxes, snuffboxes, cigarette-cases, toilet-cases and generally all articles in which particular attention had to be paid to hinges and catches; foreign masters have always admired the excellence of these Russian works, the precision of hinged lids being such that it was extremely difficult to discern the line separating the lid from the whole case, and that boxes of all kinds could be opened without the slightest sound.

Other mounters specialized exclusively in jewelry — brooches, bracelets, necklaces and tiaras set with gemstones — and also made settings for semi-precious stones, such as nephrite, rock crystal and lazurite. Although this specialization leads to technical perfection, it reduces the artistic value of the article, which passes through so many hands that it loses all trace of the master's individuality; moreover, since each specialist is concerned only with the perfection of his own operation, he tends, if necessary, to sacrifice the work of another specialist — an embosser, engraver or enameller.

Engravers were also divided into two specialties — line engraving — lettering, decorative patterns, pictures — and relief engraving produced by chiseling and grooving as for medals.

Embossers were divided into casters and chasers working with brass (…)

Silversmiths were divided into two categories — hollow-ware makers (tea services, samovars and various kinds of table silver) and mounters who dealt mostly with assembled castings (candelabras, figurines, clocks, etc.).

Since nearly all the articles were manufactured by a combination of several methods, they passed through many hands and were then assembled by specialists. Enameling and gilding operations were carried out in special workshops.

CLIENTÈLE

The court and its commissions

For a long time the main clients of the firm were the Imperial family and the courtiers, who were joined by the financial and commercial aristocracy in the 1890s. To the very last, one trait has been common to the clientele as a whole — blind worship of everything that was foreign; without the slightest hesitation, the clients would pay huge sums for articles which were inferior in quality to Russian ones, as wasevident from the fact that hardly a day passed without one of these masterpieces being brought to us for repair. An exception was Alexander III, who on principle preferred and promoted everything that was Russian.

Unfortunately at that time Russian decorative art was undergoing a period of unprecedented decline, when the so-called “rooster” style, with its flat monotonous ornamentation, was predominant.

The most typical feature of Imperial commissions was urgency: everything had to be done quickly, as though by the wave of a magic wand, and the design often had to be completed in several hours, usually at night.

The reason for this was that orders were held up at various court departments before reaching us, and we were then obliged to rescue the officials from the consequences of their negligence. We received the orders through two channels —His Majesty's Cabinet or directly from the Emperor or the Empress for private or family gifts, including the particularly interesting Imperial Easter eggs annually presented by the Emperor to his spouse.

This traditional commission, founded by Alexander III, was continued by Nicholas II who presented Easter eggs to both the Empresses. The designs of the Easter eggs were not submitted for approval and Fabergé was given complete freedom in design and execution. No less than 50 to 60 such eggs were made, and I had to assemble a good half of them. The task was by no means easy, since designs could not be repeated and the egg shape was restrictive. To make the present topical, we tried to use the family and other events in Imperial court life, naturally avoiding political events.

Nearly all these eggs could be opened and contained various little objects as surprises. The manufacture of Imperial Easter eggs was mostly very complicated, since we had to vary the materials, appearance and contents of the eggs to avoid repetitions. To give an idea of the work involved, I shall try to describe some of the eggs.

1. Egg in rock crystal, placed horizontally on an open-work pedestal in the Louis XVstyle, containing a gold tree with flowers of tiny brilliants and rubies and with a gold mechanical peacock sitting on one of the branches. When the egg was opened, the peacock could be taken out and its inner mechanism wound up, so that it strutted about characteristically, spreading its tail and then closing it. The size of the peacock from head to tail was less than 12 cm.

2. Egg designed to commemorate the inauguration of the Trans- Siberian Railway. The egg rests on a stand of white onyx decorated with the three Romanov gryphons; it is executed in green enamel with a silver band representing the map of the Siberian Railway and contains a miniature model of the Imperial train in gold and platinum. The train is powered by a mechanism concealed In the steam engine that is less than 3 cm long. The egg was decorated in Russian style.

3. Egg-clock in grape-green serpentine and pink enamel. The enameled egg is girdled with a horizontal rotating clock-face with figures in small diamonds and is supported by four serpentine columns wound by garlands of flowers in varicolored gold and standing on a serpentine pedestal. Four figures of little girls (the Emperor’s four daughters) sit on the steps of the pedestal, and on the upper part of the egg the figure of a little boy (the heir) points to the hour with a twig.

The general impression is that of a large summer-house surmounted by an egg; a group of kissing doves in white silver fly among the columns.

4. Egg commemorating the bicentenary of Saint Petersburg, gold- chased in the style of Peter I, bearing views of old and new Saint Petersburg — the House of Peter I and the Winter Palace — and portraits of Peter the Great and Nicholas II.

Inside the egg is a miniature model of the monument to Peter I by Falconet, with the granite pedestal in carved emerald. The equestrian statue is 3 cm long and 2 cm high.

5.Egg commemorating the tercentenary of the House of Romanov, gold-chased, supported by a double-headed eagle, covered with portraits of Russian Tsars and Emperors of the Romanov dynasty. The egg contains a globe in blue steel fixed on its axis, with the hemispheres bearing two maps of the Russian State in gold inlay, the first at the time of the accession to the throne of the Romanovs, and the second in the time of Nicholas II. The appearance and the contents were sometimes adapted to family events for instance, when the heir to the throne was born, the Easter egg suggested a cradle decorated with garlands of flowers and contained the first portrait of the heir in a medallion surrounded with brilliants.

During the war, Easter eggs either were not produced at all or were very modest and inexpensive, such as those manufactured in 1915: the one made for the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna was of polished steel supported by 3 steel shells and contained a miniature depicting the Emperor at the front, while the Empress received an egg in white enamel with a red cross and portraits of her two eldest daughters in nurse uniforms.

The eggs for the Easter of 1917 were not finished; someone whom I do not know proposed that they should be finished and sold to him, but the firm did not accept the offer.

Many of these works are artistically interesting because of their composition as well as their superb workmanship, and could well deserve a place in the Treasury of the Hermitage Museum.

Most Imperial Easter eggs took almost a year to complete. Work began soon after Easter and was hardly finished by Holy Week of the following year; the days just before delivery were anxious for everyone who worried that something might happen to these fragile objects at the last moment. The masters did not leave their working places until the Fabergés returned from Tsarskoe (Selo) in case an emergency arose.

Other personal orders were not so significant and did not present much artistic interest. Jewellery for dowries was usually entrusted to Bolin, while we were responsible for table silver. These festive table ornaments consisted of a central flower vase (jardiniére), several paired fruit bowls of different sizes, candelabras, champagne coolers and other objects, about 20 altogether.

We made three such surtouts de table, one for Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, another for Emperor Nicholas II and a third for Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna.

The first has already been mentioned, but the most successful was the last. The central part consisted of a domed colonnade, surmounted by a double-headed eagle and placed on a pediment with several steps; the whole complex stood on a mirror surrounded by a balustrade. Seated on the steps was a group of cupids holding a shield with a monogram. Flowers were placed around the pediment and twin fruit bowls in the same style as the centerpiece stood at both ends of the mirror tray; all the pieces were made in the Louis XVI style. The total weight was (...) poudsand the cost was (...) roubles.

With some rare exceptions, the numerous gifts that were made by the Emperors and Empresses were chosen from the stock of ready made articles, and the firm used to submit lists of items for that purpose. Official presents, ordered through His Majesty's Cabinet, consisted of snuff-boxes, cigarette- cases, rings, panagias, crosses, brooches, cuff-links and tie-pins; they were all produced at specific categories of prices.

Snuff-boxes were decorated with the portrait of the Emperor painted on ivory, bordered with brilliants and surmounted by a crown in brilliants. The snuff-boxes themselves were made of gold, decorated with chasing, varicolored gold mounting, enameling and brilliants; some snuff-boxes were made of nephrite.

Cigarette-cases were similar in appearance, except that the Emperor's portrait was replaced by a monogram.

Some panagias and crosses were of artistic interest, being lavishly decorated with brilliants and colored jewels and the central icon executed in Byzantine cloisonné enamel, chased gold or glyptics (cameos). The designs of smaller articles were rather monotonous, since the central motifs were always the double-headed eagle or the Imperial crown.

Presents given to the Emperor and Empresses were much more interesting from the artistic point of view. I shall only mention a few of them which have stuck in my memory.

The first is a silver mantelpiece clock given to Alexander III by his family on the occasion of his silver wedding anniversary, with groups of flying cupids, twenty-five in all, surrounding the clock-face; the composition incorporated the gryphons of the Romanov emblem and the emblem itself. The wax model was fashioned by the sculptor Aubert, and the work was one arshin (28 inches) high. Among the many dishes presented to Nicholas II on the occasion of his coronation, one that is worth mentioning was made of nephrite, silver-framed in the Renaissance style and decorated with enamel and precious stones; its diameter was 12 vershoks (21 inches).

A basket of lily of the valley presented to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna by the merchants of Nizhnii Novgorod was woven in gold twigs and filled with moss in varicolored gold, the leaves were made of nephrite and the flowers of whole pearls scalloped in rose-cut diamonds; the basket was 22 cm high. Nicholas II was not notable for his artistic taste and he had no pretentions to it, but his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna, was a different proposition: with her rudimentary conceptions of art and with her curiously middle-class stinginess, she often put Faberge into tragi-comic situations. She would accompany her orders with her own sketches and set the cost of the article in advance.

Since it was impossible both technically and artistically to manufacture articles according to her sketches, all kinds of tricks had to be invented to explain the inevitable changes — misunderstanding on the part of the master, loss of the sketch, and so on.

With regard to prices, the articles were sold at those she had set, in order not to incur her displeasure; since all these articles were of insignificant value, the losses were offset by her favour when important works were commissioned.

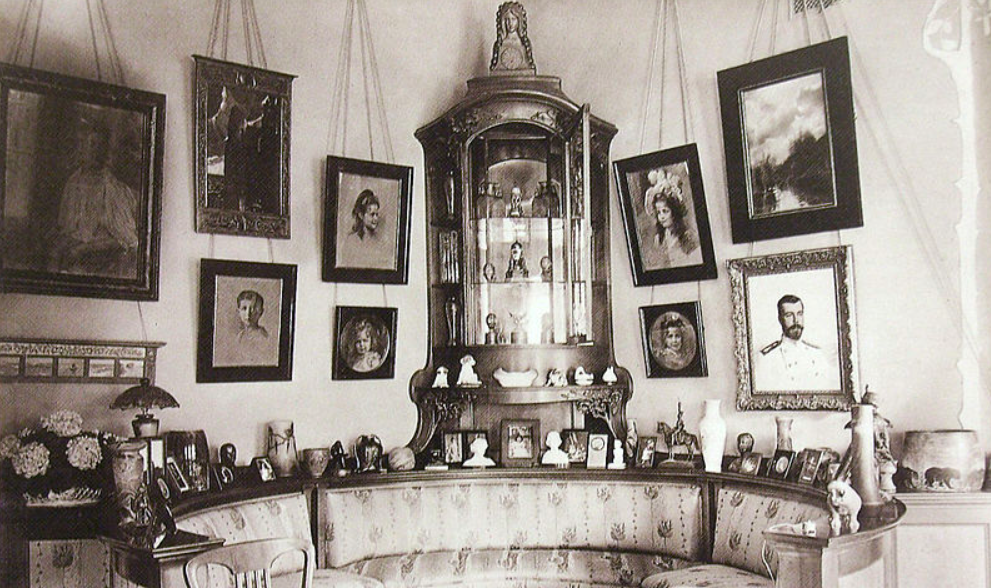

The Grand Dukes and Grand Duchesses enjoyed visiting the shop personally, and spent a lot of time choosing their purchases.

All the aristocracy of Saint Petersburg, persons of title, rank and wealth, could be seen there every afternoon between 4 and 5 o'clock, and the shop was particularly crowded during Holy Week, when everybody rushed to buy the traditional Easter eggs and to look at the Imperial eggs.

I recall one rather amusing episode in connection with Easter eggs. One of old Fabergé's clients, a lady of the high aristocracy who was not renowned for her intelligence, came to the shop several weeks before Easter and began to annoy the old gentleman by asking whether he had invented anything new in the line of Easter eggs.

It must be admitted that variations on this theme are not an easy matter and that we were all heartily tired of looking for them.

When old Fabergé grew incensed, he was not too reserved in his retorts, and he told the lady, with the most innocent expression, that square eggs would be ready in a fortnight's time. Some of the witnesses of the scene smiled, others were embarrassed, but the lady seemed to have understood nothing, and in due course arrived at the shop to make the purchases. The old man explained her, with a serious countenance, that he had really hoped to make the square eggs, but had not succeeded.

Among the members of the Imperial family, the best judge and connoisseur was Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, who would buy everything that was interesting. He not only collected antiques, but purchased everything of artistic value, irrespective of the epoch, and took delight in giving his friends objects of artistic value.

On his appearance at the shop (he never asked for things to be sent to his home for approval, but quite reasonably preferred to see everything that was on sale), all the novelties were put in front of him: uncompleted articles were sometimes brought directly from the workshop, and he would acquire them too if he was satisfied with the design.

On his annual visits to France, he always took many of our articles with him as presents, and acted as a sort of promoter of our products in influential foreign circles. Incidentally, he was one of the first to encourage Lalique with his purchases and commissions, and just as he used to take our things to France, he brought Lalique's works to Russia.

He also commissioned him (Faberge) to make a large bratina which he presented to the Moscow Regiment. Alexei Alexandrovich's precious collection was inherited by his brother Vladimir, and after his death part of it was handed over to the Hermitage Museum[1]. His Majesty’s Cabinet was always headed by military and “civilian” generals who had absolutely no knowledge of art, but performed the functions of an artistic jury in choosing designs for execution, and the results are not difficult to imagine. Of course, like most people, they liked detailed and finished designs. On the basis of this I adopted the following tactics: several variants of the design were made for each order; I would choose the design I thought the best and draw it very accurately and in great detail, whereas 1 drew those I considered to be poor less carefully. This strategy was nearly always successful, and I would receive an order for the design I preferred. In their search for economy, leading Cabinet members often used methods which were not entirely honourable: after commissioning an article from our firm, they would hand it over to some other jewellers who could duplicate it or make variants at a lower price without expenditure on the designer's work. Yet they applied to us when the orders were complicated or urgent, being sure that the work would be executed perfectly and in time.

During the last decade the procedure for obtaining Cabinet orders had to such an extent become a matter of persistence and hanging around offices that Faberge himself stopped visiting the Cabinet. The number of orders certainly decreased, but the firm was amply rewarded by the expansion of other clientele and commissions from abroad, and was able to devote its energies to more interesting tasks.

[1] — Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich’s collection of antiques was purchased for the Hermitage Museum in 1908 for 500,000 roubles. As an expert, Agathon Carlovich Faberg£ took part in appraising the collection