Eugene Faberge’s Visit to Livadia in 1912: Delivering an Easter Egg to the Emperor

By Dr. Valentin Skurlov

Fabergé Firm (manufacturer) and Henrik Wigström (workmaster), Imperial Tsarevich Easter Egg, 1912. Platinum, lapis lazuli, diamonds, watercolor on ivory, rock crystal. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA. Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt. Image courtesy of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Creative Commons CC-BY-NC..

The history of Faberge’s Imperial Easter eggs has received seemingly exhaustive treatment over the years. And yet the subject is so multi-faceted that many questions deserving attention remain unanswered. The story of the presentation of the 1912 “Tsarevich” Egg, which took place in the Livadia Palace, is but one example. As a rule, the annual Easter present — which began as a single egg and grew to two eggs in 1895 — was delivered personally to the Emperor by Carl Faberge on Friday of the Holy Week. The following day, Holy Saturday, Emperor Nicholas II presented the 1st egg to his wife, then proceeded to the Anichkov Palace to deliver the 2nd egg to his mother, the Dowager Empress Maria Fedorovna.

Livadia Palace, today.

One hundred and five years ago, in the spring of 1912, there was a break with tradition: the Imperial family were to spend the Easter holidays at the Imperial residence in Livadia, Crimea. At the Emperor’s request, Carl Faberge personally delivered the Napoleon Egg to the Emperor’s mother at the Anichkov Palace, while his eldest son Eugene (1874-1960), an agent of the company since his twentieth year, was dispatched to Livadia to deliver the second egg to the Emperor. Carl Faberge’s granddaughter Tatyana retains a copy of the 1934 letter from Eugene to H.C. Bainbridge, head of Faberge’s London outlet. At the time, Bainbridge was busy writing a biography of Carl Faberge, and he sought Eugene’s help in collecting historical material.

The letter contains a description of Eugene’s visit to Livadia:

Paris, 5 June, 1934

Dear Bainbridge,

I received your letter of the 30th and the 27th of May, as well as your book “Twice Seven,” and a copy of the latest issue of “Connoisseur,” and I wish to thank you for all of it. I have read your article in the Connoisseur and found it to be impeccable and absolutely correct. I was touched by the manner in which you described the work of my father, and I am especially grateful to you for all your kind words. I doubt a professional writer could do a better job.

There is only one error: the first egg made in lapis lazuli contained not a replica of the Cruiser “Memory of Azov,” but a frame in the form of a two-headed eagle with a portrait of the Heir Alexey. The miniature was covered on both sides with a plate of rock crystal, so that one could see the boy’s face and the back of his head. Naturally, it was decorated with diamonds.

At the moment this Egg is on display at the Chicago Expo. Naturally, you must know this photograph. The egg with the “Memory of Azov” was made in jade with gold mounts in the style of Louis XV, with diamonds in the scrolls. It was made by the old man Holmstrom, who poured his whole art into the tiny ship, to make it most life-like, with moving cannons and all the tackle a perfect copy from nature. This egg (or rather its photo) appeared in the catalog of the London branch. It is with us now… even the anchor chains move.

Other descriptions are correct. Do you not think it a pity that all these beautiful things created by my father have fallen into the hands of the Jews, who are now profiteering off them? It is a great tragedy. How did they get hold of these things? Of course, I suppose they bought them off the Bolsheviks. To be sure, I expect British Jews are people of a different sort than the Russian or Polish Jews, many of whom have become American citizens, but still — a pity… What do you think?

I gather that the brothers H [Hammer — V.S.], who have lately paid you a visit, are very fine and affable people. Perhaps in the next issue of the “Connoisseur” you will publish an article about the pretty egg with the opaque mauve enamel, with the Swan, which you mention in your book.

I am sending you a catalog of Hammer’s New York collection. The Hammers had exhibited Imperial and other finery in Chicago. Here you see the Eagle with the miniature portrait of the Heir.

This egg was made in lapis lazuli in 1912 — at that time the Tsar was staying in Livadia, near Yalta, on Crimea’s southern coast. My father wanted me to deliver it in person to His Majesty. Thus, I undertook a journey across Russia in the company of my good friend, a Finn. From Sevastopol we were driven in the Tsar’s personal automobile across the beautiful Baidar Valley and along the excellent Yalta highway; the journey lasted some 4 hours, as I recall. From there, having put on fresh clothing, I was driven in the same automobile to the Livadia Palace. An attendant took me to the Emperor, who received me very warmly. We were left alone: he was delighted with father’s charming idea, and greatly impressed with the Egg. Then he took me by the arm and led me to the window, showing me a most beautiful view of Yalta and the Black Sea, as he explained various points of interest. He then asked me to convey his gratitude to my father along with most sincere regards, and I left to meet up with my friend and dine at the hotel. After the audience with His Majesty, while still at the Palace, I met the Prince Vladimir Orlov, the Tsar’s private chauffeur, who promised to drive me the following morning from Yalta to Sevastopol. The journey (i.e., the drive) was very beautiful. That same year my father, on behalf of the Emperor, delivered an egg to Maria Fedorovna, who had stayed in St. Petersburg.

I am sending along answers to your questions. I hope you will find them satisfactory. If you need any other clarifications, please write to me. I will do my best to supply them. I am not a writer either; all I can offer are bare facts. Once more, I thank you. Yours sincerely,

[no signature]

Mr. Hammer, the younger, visited me a few months ago, and sent me some photos of our Easter eggs. If you wish, I can pass them along to you. He had spent 7 years in Soviet Russia, and speaks Russian well. To be sure, he used every opportunity to buy up artworks, icons, Faberge pieces, etc., which he is now selling…” [1]

To be sure, the lapis lazuli egg of 1912 was not the first to use this beautiful and costly stone: it had appeared in Imperial Easter eggs made in 1909 and 1910:

The Imperial Standart Egg of 1909. Photo Dmitry Korobeinikov, Sputnik.

1909. Empress Alexandra Fedorovna. Standart Yacht Egg. The egg and its pedestal are of rock crystal. Dolphins and middle section of the pedestal are of lapis lazuli.

Alexander III Equestrian Egg, unknown photographer.

1910. Empress Maria Fedorovna. Alexander III Equestrian Egg. The egg is of rock crystal, inside a replica of the monument to Alexander III on a pedestal of lapis lazuli. [2, 192] The pedestal was made at the Peterhof Lapidary Works, for which a special dispensation had to be obtained from the Minister of the Imperial Court, since the manufactory was barred from accepting private orders.

Still, these were only distinct elements in eggs made of other materials. The first egg made entirely of lapis lazuli was, indeed, the egg of 1912. The rich color of Badakhshan lapis lazuli emphasized the maritime motif of the egg: the miniature, painted by V. Zuev, pictred the Tsarevich in naval uniform, as the child was enrolled in the Naval Guards Corps since his birth on August 11, 1904.

The provenance of the 1912 Imperial egg is documented in literature: [1, 208]

Livadia Palace, 1912. In the spring of 1912 the Imperial family once again remained in Crimea for several months, returning to St. Petersburg on June 10, 1912.

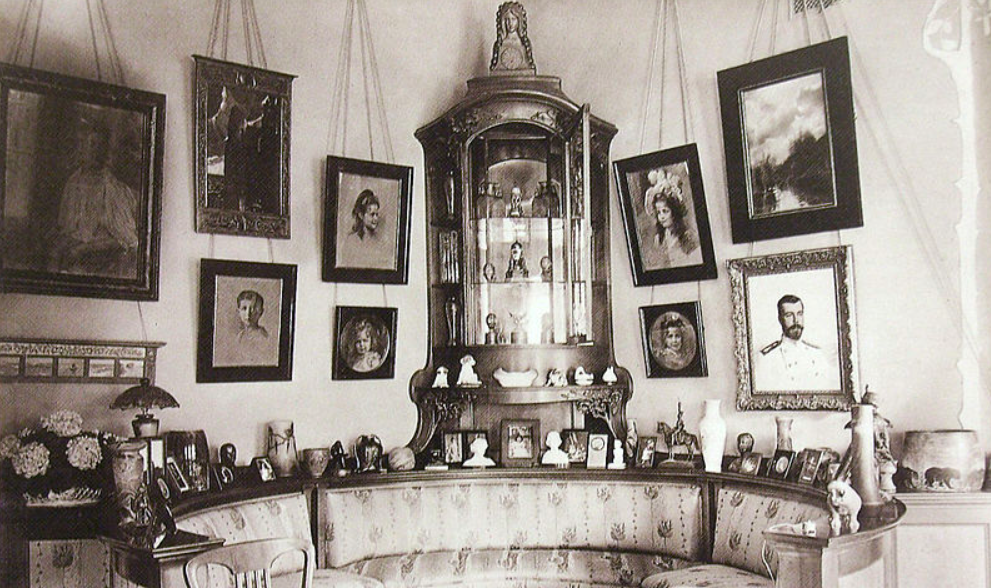

The Empress Alexandra Fedorovna’s Maple Room at the Alexander Palace, 1912-1917.

September 16-20, 1917 — transferred from St. Petersburg to the Armory Chamber, Moscow.

February-March, 1922 — transferred to the Foreign Currency Directorate of the NarKomFin.

June 17, 1927 — Returned to the Armory Chamber of the Moscow Kremlin and assigned inventory number 17547.

June 21, 1930 — Transferred to the foreign trade organization Antikvariat, to be sold to Armand Hammer. [2, 208] Hammer claimed in his book that he paid 100,000 rub ($50,000) for the egg. In reality, it sold for a mere 8,000 rub ($4,000). [3, 80]

The Imperial Eggs displayed in their cabinet in the Maple Room at the Alexander Palace. The Tsesarevich Egg is on the first shelf, at right of the Standart Egg.

In 1927 a commission headed by Prof. S.N. Troinitsky, director of the Hermitage, academician A.E. Fersman, gemologist A.F. Kotler, diamonds specialist Dmitriev, jeweler Krivtsov and accountant Bedrit, undertook a valuation of the 1912 Egg for potential sale through Antikvariat:

“Weight: 574.2g; dimensions: 12.1 x 8.7cm; eagle 9.8 x 5.7cm; table diamonds 1 car — 60 rub; diamond 0.8 car — 100-80 rub; lapis lazuli — 200 rub; gold — 200 rub; 1,835 rose-cut diamonds at 1.25 rub each — 2,293.75 rub; glass — 1 rub.25; ivory — 6 rub.

Total cost of materials — 2,841 rub. Labor 25%. Total materials and labor — 3,551.25 rub. “Antique” markup coefficient — 4. Minimum price in the 1st category — 14,205 rub.” [4, 10]

The “antique” coefficient was applied in valuations of artworks by masters no longer living, who, in consequence, could not reproduce their work. The markup, moreover, took into account the historical significance of the piece, which had belonged to the last Russian Emperor.

It should be noted that the actual price of the Egg in 1912 was 15,800 rub. [5, 40] The experts valued the labor at 25% of the cost of the materials — a very low valuation. They, moreover, completely failed to take into account the value of the original idea, design, technical drawing, project and shop supervision. This is in contrast to the value placed on artistic work by Faberge. Such principals as the chief workmaster and artistic director Franz Birbaum or Ivan Antoni (supervisor for Imperial commissions) received a monthly salary of no less than 250-300 rub. As Franz Birbaum notes in his memoirs of 1919, the work on Imperial Easter eggs went on for a full year. “Begun shortly after Easter, they would scarcely be ready by Holy Week. They were then presented personally to the Emperor by the head of the firm on Friday of Holy Week.” [6,19] Evidently, workmasters on such a commission would stand to receive a year’s worth of salary. Vasiliy Zuev could earn at least 300 rub. for his two-sided miniature (face and back of head). The experts also failed to note that the diamond eagle is made not of gold but of platinum, which cost twice or three times as much as gold, while the application of diamonds to platinum should be valued higher, as the work is more difficult. Even at the labor rate of 25% of the cost of material, the application of 1,835 rose-cut diamonds would mean 460 rub for that work alone. Costs associated with the assay control process are likewise ignored, along with other overhead costs, such as delivery to Crimea. It seems that the commission did not consult any of the master jewelers, who had worked for Faberge and knew the prices commanded by the workshops of Wigstrom, Kremlev and Holmstrom. These were often two to three times higher than the rates offered by other workshops in St. Petersburg. The price of 8,000 rub. in gold that Armand Hammer paid to Antikvariat in 1930 is, in fact, close to the item’s actual cost of production: it is just over half the amount (15,800 rub.), which the Emperor paid to Faberge.

Until quite recently, cautious readers gave little credence to the intuition of certain researchers concerning the authorship of miniatures in Imperial Easter eggs. The painter of the miniature in the 1912 Tsarevich Egg was considered unknown. In September of 2013, T. Muntyan, research associate at the Kremlin Armory, published a paper that included excerpts from the Faberge Accounts book [7, 140], discovered in 2006 in the Russian State Archive. These excerpts — descriptions of the Imperials Easter eggs of 1912, 1913 and 1914 — were subsequently republished in an antiques journal. [8, 77] In September of 2014 we were able to publish in “Russian Jeweler” descriptions of these same eggs that listed Vasiliy Zuev as the painter of the miniatures included in four of those eggs [9, 7]:

“24/III 12. LARGE EGG in the style of L[ouis] XIV in lapis lazuli, ornam[ented] with ch[ased] mat[te] g[old], 1 bril[liant] and 1 l[arge] rose. Inside two-headed eagle in plat[inum] with 1871 r[oses] and a two-s[ided] miniature of HIH the Heir Tsesarevich, by Zuev… 15,800 [rub].” [5, 40]

The collection catalog of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts for 1995 contains the following description of the 1912 Egg, written by the curator David Patrick Curry:

Fabergé Firm (manufacturer) and Henrik Wigström (workmaster), Imperial Tsarevich Easter Egg miniature, 1912. Platinum, lapis lazuli, diamonds, watercolor on ivory, rock crystal. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA. Bequest of Lillian Thomas Pratt. Image courtesy of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Creative Commons CC-BY-NC.

“The original double-sided miniature with a watercolor portrait has suffered damage and is still in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The current portrait on display is an archival photograph. Inside the egg, an engraved golden disc with a rose window design serves as a platform for the portrait frame.”

The miniature portrait of the Tsarevich in naval uniform survived, but in damaged form, which led the Museum to replace the original watercolor miniature on ivory with an archival photo. [10, 81-81] The miniature is unsigned. [10, 78]

The Museum is perfectly frank about the location of the original miniature. They have replaced it with a photo so as not to disappoint their visitors. Curiously, the curator writes that the painter of the miniature is not known. At the same time, the name of Vasiliy Zuev did not come to light until the publication of the original invoice by T. Muntyan in late 2013.

The stand is lost, but is known from a 1953 publication by K.A. Snowman. [11, ill. 336, 337, 388] and is similar to the stand for the 1911 “Fifteenth Anniversary” egg.

Only one other example of this type of double-sided miniature — face and back of head — is know from that period: seven portraits of the children of Alexander II and Maria Alexandrovna, artist unknown (ca. 1860s). [12, 52]

Western scholars have misinterpreted the artistic conceit of the Egg, supposing that it references the miraculous recovery of the Tsarevich following a hemophilic crisis that occurred in the fall of 1911, while the family resided at the Spala Imperial Lodge in Poland. The boy, it is said, came very close to dying, but ultimately recovered. In reality, this crisis took place in the fall of 1912. We can only conjecture about the event this egg was meant to commemorate. There was one major anniversary in 1912 — it marked the Empress’s 40th birthday — but the Empress would presumably wish to avoid any allusion to that date. It is well known that the design for each egg was developed by Carl Faberge and his creative team. “These drawings (for Imperial Easter eggs) were never submitted for approval. Faberge had complete creative freedom,” noted Franz Birbaum, who had personally saw half of all the eggs through the production stage. [6, 18] While we have no cause (or right) to complain about the design of the Tsarevich egg, we still want to know what meaning or mystery lies at its foundation.

A few words about Lillian Thomas Pratt (1876-1947), wife of a General Motors executive and one of Armand Hammer’s five American clients. Pratt was an avid collector of Faberge from 1933 through 1946, with a collection comprising some 150 individual pieces, from Imperial Easter eggs to a brass ashtray. In 1947 she bequeathed her collection, which included 5 Imperial Easter eggs to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. This is the third largest collection of Imperial Easter eggs, after those of the Kremlin Armory in Moscow and the Faberge Museum in St. Petersburg.

It would be worthwhile to continue research into Eugene Faberge’s visit to Livadia, and to discover the significance of the design of the Tsarevich Egg. Which stone carver carved the lapis lazuli egg (was it Petr Kremnev?), and who made the platinum eagle with diamonds (Holmstrom’s workshop?). What was the production cost of the egg? Who is the Finn that accompanied Faberge on his trip to Livadia? Could it have been Henrik Wigstrom? We must find the paperwork documenting Armand Hammer’s dealings with Antikvariat in 1930-33. How did the miniature portrait of the Tsarevich come to be damaged? And there are many more questions of varying significance and specialization, which can shed light on the relationship between the Imperial family and the jeweler Carl Faberge.

References

1. Arkhiv Tatiany Faberzhe. «Delo Perepiska E.K. Faberzhe. Raznoye. 1930-e gg» [The Archives оf Tatiana Fabergé. Case «Correspondence оf E.K. Faberge. Different. 1930].

2. Fabergé T., Proler L.G., Skurlov V.V. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs. London: Christie’s, 1997. 272 p.

3. Hammer Armand. The Quest of Romanoff Treasure. New York: William Farkuhar Payson, 1932. 184 p. ill.

4. Otdel pis’mennyh i arhivnyh istochnikov GMZ «Moskovskii Kreml’» [Department of written and archive materials of state reserve museum «Moscow Kremlin»], f. 20, op. 1927 year, d. 20.

5. Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii (GA RF) [State archive of Russian Fedration], f. 1463, op. 3, d. 3194.

6. Birbaum F. Kamenno-reznoye delo. yuvelirnoye i zoloto-serebryanoye proizvodstvo firmy Faberzhe (rukopis 1919 g.) [Stone- carved case, jeweler and gold and silver production at Faberge (manuscript 1919)]. Istoriya firmy Faberzhe [The history of Faberge]. Published by T.F. Faberzhe and V.V. Skurlov. Saint Petersburg, Russkiye samotsvety Publ., 1993, 102 p.

7. Muntjan T.N. Proizvedenia firmy Karla Faberzhe v sisteme pridvornogo byta konca XIX – nachala XX vekov [Masterpieces of Faberge in system of court life, end of the XIX – beginning of the XX centuries]. Dinastia Romanovyh v kul’ture i iskusstve Rossii i Zapadnoi Evropy. Istoriia i sovremennost’: materialy mezhdunarodnoi nauchno-prakticheskoi konferencii. Perm’ – Cherdyn’ – Nyrob [Romanov’s House in culture and art of Russia and Western Europe. History and modernity: materials of international theoretical and practical conference. Perm – Cherdyn – Nyrob]. Perm, 2013, pp. 132–145.

8. Muntjan, T. Simvoly ischeznuvshei imperii [Symbols of the extinct empire]. Antikvariat, predmety iskusstva i kollekcionirovania [Antiques, items of art and collecting], 2013, no. 12 (112), pp. 74–79.

9. Krivoshei D., Skurlov V., Faberzhe T. Buhgalterskaja kniga Faberzhe za 1910–1916 gg. [General ledger of 1910–1916 years]. Russkii Juvelir [Russian Jeweler], 2014, no. 3, pp. 6–7.

10. David Park Curry. Faberge. Virginia Museum of Fine arts. Washington: University of Washington Press, 1995. 118 р.

11. Snowman A.K. The Art of Carl Fabergé. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1953. 168 р.

12. Christie’s Fine Russian Works of Art. Geneva. April 12. 1988, No 86. Sem’ portretov detei Aleksandra i Marii Aleksandrovny, khudozhnik neizvesten [Seven portraits of the children of Alexander and Maria Alexandrovna, artist unknown].

13. Faberge Eggs: A Retrospective Encyclopedia (Hardback). By (author) Christel Ludewig McCanless, by (author) Will Lowes. Lanham, Mariland, and London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2001. 286 p.